While the ER physician suggested Patricia might be dying, the patient’s granddaughter, Tiffany, took offense. Patricia was 87 years old and had been slowing down over the past six months. She had experienced diminished appetite and lost interest in living. She was brought to the emergency department for evaluation and diagnosed with pneumonia.

Patricia seemed to be nearing the end of life, yet she had no significant medical problems. Her daughter, Sandy, looked after her and was concerned about how much she should be doing to help her mom. Patricia sick? This was new to Sandy. Nevertheless, due to age and the doctor’s diagnosis, it was important for the ED physician to inquire about whether Patricia had a living will or advance directive in place prior to hospital admission. If need be, would Patricia be placed on a ventilator? Would CPR be initiated if her heart stopped?

Tiffany believed this type of conversation was out of bounds for Patricia to hear. She wanted to take it outside and verbally brawl with the physician in the hallway. Sandy was torn between both sides of the argument and did more listening than speaking. The resolution: Tiffany and Sandy agreed to wait and see if Patricia needed resuscitation. She would be a ‘full code resuscitation’ until cooler heads prevailed.

If finding yourself in a similar situation, these four tips may help blunt the defense mechanism of anger:

Anger often erupts out of sensitivity

As caregivers handle stress, they build sensitivity and resilience – feelings that easily be offend or hurt. Tiffany was more sensitive and reactive regarding her grandmother, while Sandy portrayed resilience. However, the physician needed Sandy to be more responsive and ask further questions. For example, “What are the pros and cons of my 87-year-old mother being resuscitated?”

Allowing yourself to be too sensitive becomes high risk for your patient; you never want to make medical decisions for them out of misunderstanding or anger. Caregivers must use discretion in matters of life and death while acting from the position of authority – ‘being the adult.’

Patients do not expect to die until they are awakened to the prospect. It’s important for caregivers to maintain high watch for impending disaster and avoid overreacting. Her granddaughter and daughter personified the internal conflict Patricia herself was battling. She had the right to be resuscitated, but did she intend to let her ‘inner Tiffany or Sandy’ have the last word?

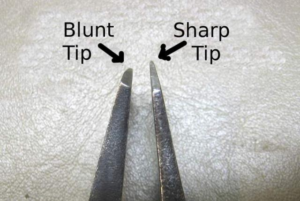

Anger sharpens the double-edged sword

Anger stirs passion and can harm your patient. It can make you care too much, or not at all. Anger is ex

hausting and can prove to be counterproductive. Healthcare providers often tune out caregivers and dismiss them as being “irrational.” This leads to feeling helpless. The saying, “Don’t bite the hand that feeds you” is a good rule for anger management. As a caregiver, primarily focus on composing yourself, asking questions and remaining open-minded.

Become more balanced and blunt your anger. Don’t sharpen the edges of anger’s sword by only seeing one side of the situation. Remain open to life’s transitions and increase your understanding of both sides of the end-of-life conversation. You need the capacity to advocate for life or death, depending on the situation.

Anger indicates fear

Most caregivers are afraid of doing something wrong themselves or having others harm their patients. Fear provides a healthy alert: “Warning! Warning! Your patient’s life is in danger!” It also guides your conscience: “I am called to do the right thing.” When acting out of fear, you have the choice to feel helpless or to pay reverence. Anger stirs up impassioned emotions, while fear calls for an awakening.

Tiffany’s emotional upset did not help her mother or grandmother. While studies indicate the futility of resuscitating an elderly patient, there seemed to be no interest in pursuing this concern. Although Tiffany did not have healthcare power of attorney, she was both the most outspoken and least willing to listen. Potentially, Patricia could suffer negative consequences.

Anger calls for a timeout

You might say ‘emergency visits’ and ‘heated arguments’ have similar patterns. There is an emotional response to initial assessment followed by further questioning and reassessment. The time in between allows everyone to gather their thoughts, review the situation and formulate a definite plan of action.

Tiffany was given a moment to sit with her emotions about her grandmother, but she chose not to resolve this upset. She may have won the battle, but would she win the war? If you spend the time stewing or digging in your heels, you have not used this time effectively.

People are prone to react when upset, but upon further consideration often end up wishing that we had responded differently. As a caregiver, allow yourself a timeout with permission to react and respond to any given situation. This time allows you to move from being human to be becoming heart-centered.

—————————-

Fear can become your best friend or your worst enemy. While anger may get the best of you, fear can allow your conscience to be your guide. By understanding what you are afraid of as a caregiver, will allow you to gain an appreciation of your patient’s fear. Help guide your patient through the end-of-life journey by managing and blunting your own anger.

Leave a Reply